[The above video is mostly a

reading of the text below, with an occasional aside thrown in for good measure

as they strike me as relevant. I welcome questions, comments, or concerns about the material contained in

this video.]

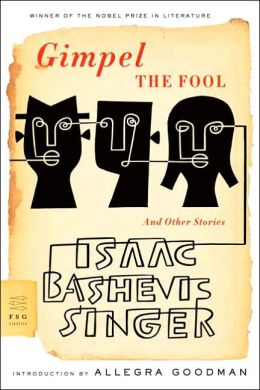

“Gimpel the Fool and Other Stories” was originally published in 1953, and contains ten short stories rife with Singer’s unique fictional voice – full of meditations on mortality, good, and evil, Jewish mythology, and an ability to communicate truths in the folksy, simple yet extraordinarily sophisticated way that characterizes these parabolic stories. Singer’s protagonists live in the Old World in every sense - a world inhabited with dybbuks, qlippoth, and golem who are every bit as real as anyone else. They are not disembodied spirits in “the world beyond.” They quite literally live in your mirror (see “The Mirror”) and come to talk to you after they have died.

In the title story, and maybe one of the more endearing, Gimpel, a baker from Frampol, openly declares in the opening lines “I am Gimpel the Fool. I don’t think myself a fool. On the contrary. But that’s what folks call me.” His innocence and simplicity almost set him up for the reader to expect something more sinister, but his child-like nature abides. Despite marrying a woman who shamelessly cuckolds him time and time and time again, he seems to have a preternatural ability for forgiveness and acceptance. One night, a Spirit of Evil visits him in his sleep and tempts him to deceive the world in the same way that it continues to deceive him. He asks how, and the Spirit responds “you might accumulate a bucket of urine every day and at night pour it into the dough. Let the sages of Frampol eat filth,” and urges him not to believe in God. The spirit of his wife visits him and warns him that just because she was false to him doesn’t mean that everything he’s learned is false. Gimpel is a poignant figure, but one whose goodness consigns him to what others think is foolishness for his entire life.

Singer the parabolist is at his height “The Gentleman from Cracow” wherein a man descends upon Frampol seemingly able to solve many of the city’s problems with his tremendous generosity and wealth. The only man trying to brook his influence on the townspeople of Frampol is old Rabbi Ozer, who keeps warning that he is a satanic influence. With such a heavy-handed theme, Singer does the seemingly impossible here: telling a moralistic tale without taking a cudgel to the reader’s head in order to communicate his message. This might be one of my favorite stories in the collection because its tone has so much in common with many of the others. It is a clearly articulated, well-defined fable that leaves enough room for ambiguity to entice the intelligent reader to visit it more than once.

After this and a couple of other experiences with short stories this year, I think I could reconsider what I think of them. Both this and Angela Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories” are two of the best books I’ve read in the last year. I was in the bookstore the other day and bought “In My Father’s Court,” an autobiographical volume about Singer’s rebellious childhood. These stories more than anything else struck me as the stories of a rebel; the characters are overly credulous yet smart, and deeply religious but speculative and doubting. If it’s anything like these stories, I can’t wait.

No comments:

Post a Comment